I’ll be doing this in english, as this answer originally was done in english as a respons to statistics being presented to my group of emergency physicians, in Stockholm, Sweden.

This series of Q&A blogs, are written without great peer review, and should be though of as quick-and-dirty answers to real life questions and problems we face as emergency physicians.

This time it’s about the 4h rule and “quality” measures in healthcare

Background knowledge and the “input” situation in the ED in Stockholm

For background knowledge of how the swedish system works, I have done several blogs on this:

- https://akutmedicineren.dk/erfaringer-fra-stockholm-introduktion/

- https://akutmedicineren.dk/erfaringer-fra-stockholm-del-1-det-frie-vaardval-og-lande-vi-sammenligner-os-med/

- https://akutmedicineren.dk/erfaringer-fra-stockholm-del-2-tribalism-tid-til-at-lytte/

- https://akutmedicineren.dk/erfaringer-fra-stockholm-fejlkultur-og-resuswankers/

In Denmark with our uniquly excellent primary care , who provides contious care for the patient and a system that follows the LEON principle (especially outside of Copenhagen), some of the problems the world is seing in the ED are not as relevant because we are to a greater extend capable of

- Arranging quick follow-up for our patients with their GP

- Having less anxious patients: The patient is in contious contact with their GP meaning one doctor / one GP-practise, knows the patient. This creates an envoirenment where the ED can work as it was supposed to – ruling out emergent problems, not having to go beyond the responsibility of emergency medicine of 1) ruling out time-critical problems and 2) reducing suffering (through for instance pain-medication, good communication etc)

- Following the LEON principle: patients with GP-level problems in the majority of times stay at the GP-level (maybe to a lesser extend in Copenhagen because of the 1813 pathway into the hospital). Anything else is ineffective and potentially dangerous for the patient (overdiagnosis and risk of comission)

Despite our cultural similarities, the swedish healthcaresystem, and especially the system in Stockholm , however does not resemble the Danish/norweigian model in several important ways (se blog-links above).This is primarily because of political ideological changes through the 80’s where “moderaterne” (liberals), changed the system more towards an american model, encouraging the privatization of health care and introducing the “fria vårdval” where patients can go whereever they want for healtcare (several different GP’s in one day and the ED). Now this has escalated (even before C19), with the “Nya Karolinska” (NKS)-scandal, with for-profite telemedicine GP’s (i.e Doctor24 , KRY and Doktor punkt se) and the vast introduction of management models from the business-sector (i.e New Public Management (NPM) or similar economy/business inspired management models such as “Value based health care” in NKS and LEAN in other locations ).

“Quality” measures and Taylorism: paradoxically creating low value care

Systems engineer Paul Plsek compares throwing a stone with throwing a live bird. The trajectory of a stone can be calculated precisely using the laws of mechanics, and it is possible to ensure that the stone reaches a specified target. However, it is absolutely not possible to predict the outcome of throwing the live bird, even though, in truth, the same laws of physics govern the bird’s motion through the air. As Plsek points out, one solution would be to tie the bird’s wings, weight it with a rock and then throw it. This will make its trajectory nearly as predictable as that of the stone, but in the process the capability of the bird is completely destroyed. This seems very close to what happens when we try to measure the quality of healthcare using measures that ignore the presence of human subjects either as patients or as healthcare professionals.

Iona Heath, Arm in arm with righteousness

At the moment we waste effort, money and time, collecting data and pursuing quality targets, so that we have less time to listen and we risk losing sight of the suffering human subject. And we risk destroying quality in our attempt to measure it [opportunity cost]. It is time to untie Plsek’s birds

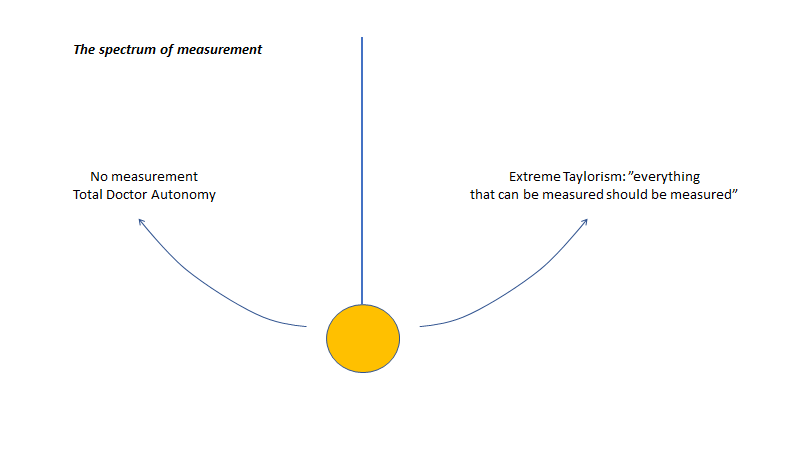

With this introduction of business-inspired management models decades ago, a philosophy known as taylorism (everything that can be measured should be measured) was introduced. This excellent EmCases WTBS-blog series explains:

The pendulum swung from a place of complete physician autonomy to one where measurements encroached on clinical care (“did you spend longer than 15 minutes with any patient today?”) and personal freedoms (“you were timed as having taken a long bathroom break today”). This has unsurprisingly created tensions between administrators and front-line providers, who are pushing back against the use of these measurements quite hard.

Dr Howard Ovens: WTBS 6 Measuring Quality – The Value of Health Care Metrics

If you want a weighted argumentation on this topic, the abovementioned WTBS 6 blog is a good place to start.

I, however, will probably not give a 50:50 weighted argumentation on this topic (i do believe some measurements are OK, but these should be closely choosen by clinicians and patients in order to not suffer opportunity cost and “measuring for micromanage / measurings sake”). I believe that topics such as overdiagnosis, opportunity cost, reverse robinhood effect and huge conflicts of interests are harming the patient (and the doctor…and the economy) way too much in modern medicine. Measuring and Taylorism is a big part of this complex net of massive problems of abundance that in later years have gone haywire. I believe the pendulum should be swung beyond the 50:50 line towards doctor autonomy, because we are experts. We have an expertise that cannot be “learned” in just 5 minutes of googling (the art of clinical judgement and EBM cannot be learned in 5 minutes). That’s our job and the society wants us as experts for this – for the sake of the patient, as their protector and advocate. No one has ever made this “fiduciary”-argument better than Dr Hoffman 10:00-17:00 (it is well worth a listen / view!)

I am also growing more and more nihilistic in my believe in what modern medicine in its current form, actually can help the majority of patient with. Our main job is to find the diagnosises that we do have a good treatment for in accordance with EBM.

If you wonder why my nihilism has grown lately it has to do with several books and lectures. Amongst other these: EBM 2.0, Bad Pharma (summed up in this lecture) and The Danger within us

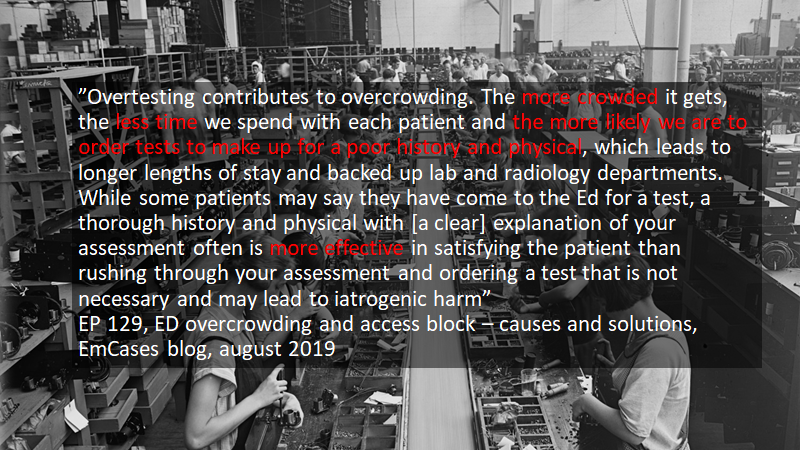

As always – communication and compassion for the patient has the lowest NNT/NNH ratio of all (besides being our most valuable diagnostic tool – when done well – to avoid premature closure), and is unmeasurable in Taylorism!. For one of the strongest updates on this, please do yourself a favor and check out this post-humal podcast with Barbra Tatham

https://emergencymedicinecases.com/physician-compassion-barbara-tatham/

Back to Taylorism, and the concept of “measuring” Vs “not measuring”:

If you want to read one or three articles about this from a different perspective these three are great. Firstly by Iona Heath (“arm in arm with righteousness”)

https://peh-med.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13010-015-0024-y

Secondly this by Bjørn Morten Hofmann (Too much Technology)

https://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/891375?path=/bmj/350/7996/Analysis.full.pdf

and this legendary article and podcast by Jeffrey Braithwaite in complex systems, failure culture and the importance of feedback in complex systems (BMJ: changing how we think about healthcare improvements)

https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k2014

I am working on a blog to explain how Taylorism and NPM are very important to understand for doctors, as this (along with the medical-industrial-complex i.e big pharma and the device industry) are among the main reasons why medicine is becomming overly expensive and bloated with overdiagnosis, unrealistic expectations from policy makers (and therefore influencing the public and patient-organizations), lobbying by the forementions industry-complexes and absurd amounts of conflict of interests, corruption and the resulting low value care, with medicalization of the public and the unneeded suffering that insures from it. The worst being the opportunity cost – vast amount of energy, time and money lost on following the entirely wrong idea of what healthcare looks like – or as Iona Heath puts it: every act of overdiagnosis is underdiagnosis somewhere else in the system.

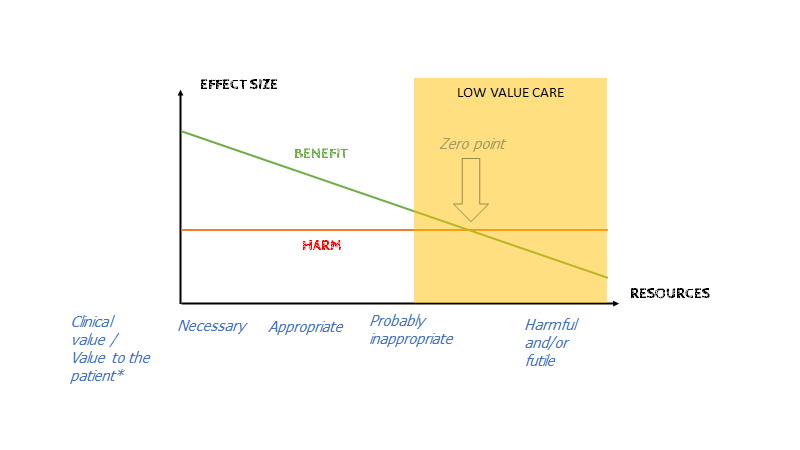

Harms of a treatment are constant (no matter if you have a big or a small bloodcloth, your risk of bleeding on NOAK is the same). But Benefit is decreasing as we test more and more (in ressource rich settings where everything can be tested always). What we are now facing is the tipping point in many cases, where harms > benefit in many treatmens (especially with “indication creep”)

In one sentence: for profit healtchare inspired by the business-sector (i.e NPM, medico-industrial-complex etc) creates a system with confusing and often absurd priorities in the compelx healthcare system – Not only in science, but also in clinical work where the doctor is often put in a position where he/she has to choose between 1) what’s best for the patient, 2) what’s best for the doctor (risk proximity, guidelines and “standard of care”) and 3) what’s best for the economy

Examples of this will ensure in the anwer below

The 4 hour rule (as an example of a surrogate quality measure)

In my hospital, our group of emergency physicians do sadly not have ownership over the emergency department. I work at a private hospital (on the outside looking like a normally run public hospital – you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference), where the 4h rule is king.

The 4 hour rule is an idea that has been mainly introduced to ED’s in the UK, and to some extend in Australia and North America. In short, if your patient stays in the ED for >4 h (i.e “breaks the 4 hour rule”), the hospital does not get paid for that patient. This is supposed to be a quality measure, but is the prototypical example of how an idea from business-models introduces a linear solution (getting waittimes down) does not fit a complex problem (waittimes in the ED) – i.e trying to bind Plsek’s bird (se quote above) or trying to make patients (multidimensional and complex humans) into Toyotas (simple machines).

The ensuring absurdity of not paying a hospital if they are doing bad is fundementally problematic, as it creates a reverse robin hood effect (it incourages hospitals to only take on simple, easy, quick patient-cases – people who are often in the middle or higher in the socio-economical pyramid. This leaves patients in the lower half of the pyramid, who often has complex problems and lack of ressources to deal with them, penalized).

It has close ties to the “access-block / crowding” problem, and is falsly believed to be under the control of the emergency department. People with experience with the ED complexity, will understand that the 4 hour rule and the access-block problem is just a symptom of a sick system, and the solution goes far beyond the ED (even though this is where the problem “seems to be”, as we are both the front door to the hospital, and the safety net of the health-care system)

Avocado patients: The Complex patients that no-body wants in Taylorism healthcare

Avocado patients: In our group a term has emerged for these unfortunate patients, that are complex and does not fit neatly into any box or department slot: avocado patients. The term comes from the anaology, when you are shopping for avocados. The more people who has pressed on a patient, the fewer wants it, and the worse it gets. The same is the case for these complex patients in the ED. Disposition is always hard, and if they are critically ill, and no one wants them (because they don’t fit into “surgery” or “medicine” or “orthopedics” – for instance the multimorbid elderly patient with falls because of pneumonia with hipfracture and a small subdural bleed – requires longer admission than 48h and is not sick enough for ICU…hell let’s just say they have a bit of fever and cannot be ruled out for COVID19 and no isolation-room exists). The NEWS score (or whichever triagescore you are using), does not show how long time a patient is going to take to manage in an ED envoirenment. I therefore propose, that a Avocado-score is instituted to explain the complexity of the patients problem (complexity is the new acuity in the ED. Earlier the triage-score determined if a patient took a long time, but more and more, their complexity does (PS: be aware of the depersonalizing nature of calling patient’s “avocados”. I am using it as an anology, but in general such depersonalizing terms should not be used for patients)

Bottom line: the 4 hour rule (amongst other – and like most linear quality measures blindly applied to complex systems) makes it seem like all patients are equally easy to manage. If a patient has vague symptoms (low news) and a “high avocado / complexity score”, this patient is a hard “sell” (Nugus og braithwaite et al, 2010: The sell, BMJ). If “complexity” was measured along with the 4 hour rule it might be a slightly more realistic measure of performance

The question(s)

My group gets weekly statistics of how well we are doing on reaching the 4-hour rule-target. And through the last 2 years (2018-2020) it has gone down, meaning less and less patients are being managed within 4 h (an event co-inciding with the introduction of emergency medicine with emergency physicians partly staffing the ED as a concept at our hospitals). The picture that seems to be painted is that of “4h rule being broken more and more, coincides with the introduction of emergency medicine as a concept – therefore they must be causally connected (i.e we are the reason for the 4 h rule being broken more than earlier)”.

Question 1: Is the 4 hour rule a good idea? (partly answered above – in short: probably not, if not designed by clinicians in feedback-loops, see Braitwaite et al,2018: changing how we think about healthcare improvements)

Question 2: If the 4 hour rule is being broken more and more often, who is to blame? (see below)

The rest of the blog, is my answer to our leaders. I know you might not be interested in the partiularities of my hospital, and I have erased these. However I think it serves as a general example of what many emergency physicians faces, not only in NPM/business-model-run systems, but also in the public sector. This is an example of

- How we as emergency physicians often are undervalued when looking on narrow “quality” measures from business-models / NPM (think in Denmark of the “accreditering” and “the danish quality model” a couple of years back – these things exists everywhere, as NPM, as a trojan horse has become the standard in many healthcare administrators management plan)

- How our expertise is often not understood / misunderstood by the healthcare community

- How dominant top-down management is not a fitting model in complex healthcare settings (feedback loops and ground up solutions are)

- How linear quality measures are a bad way of assesing quality in hospitals, when working with complex patients

Systems engineer Paul Plsek compares throwing a stone with throwing a live bird. The trajectory of a stone can be calculated precisely using the laws of mechanics, and it is possible to ensure that the stone reaches a specified target. However, it is absolutely not possible to predict the outcome of throwing the live bird, even though, in truth, the same laws of physics govern the bird’s motion through the air. As Plsek points out, one solution would be to tie the bird’s wings, weight it with a rock and then throw it. This will make its trajectory nearly as predictable as that of the stone, but in the process the capability of the bird is completely destroyed. This seems very close to what happens when we try to measure the quality of healthcare using measures that ignore the presence of human subjects either as patients or as healthcare professionals.

Iona Heath, Arm in arm with righteousness

At the moment we waste effort, money and time, collecting data and pursuing quality targets, so that we have less time to listen and we risk losing sight of the suffering human subject. And we risk destroying quality in our attempt to measure it. It is time to untie Plsek’s birds

The Answer

Introduction

The problem with increased wait-times despite of lower input (less patients attending the ED) is a complex one (https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k2014 ), and therefore has to be viewed from different angles. To think that changing one thing, will change the course of the problem is at this point in the evidence litterature on complex systems, naïve.

In the following we have put some general statements inspired from the crowding-litterature- and the complexity litteratue of which there is abundancy in Emergency Medicine Academia and FOAMed. Especially the UK who also has the 4 hour rule target and vast problems with holding that target are forefrunt runners and much of the litterature comes from RCEM (Royal College of Emergency Medicine)

We have applied the litterature to our setting in [our hospital], through the help of our collegues and our own experiences.

Our central messages are

1: Crowding / Boarding and incrased wait-times in the ED is by now known in the litteratue to be

A whole-of-hospital and whole-of-system approach!

This implies that even though crowding and increased wait-times are seen in the ED they are not primarily a ED problem, but a problem with the entire system. Therefore solutions should also come from the entire hospital- and system in collaboration with resources allocated to the ED. Examples of solution from the UK has been 1) greater collaboration between the ED and the departments, 2) Stopping the time in the ED, when the patient is “ready to be admitted”, and from then on the time “belongs” to the department, and they are the ones getting “punished” if they break the time-barrier, 3) Having coordinating doctors / nurses who find spots for the patient, and checks in with teams when a patient is on the way to break the 4-h barrier and see if it can be helped

2: The 4 hour is with very little (if any) evidence of “patient quality” in the litterature. Oftentimes patient quality and the 4 hour target comes into conflict with each other, resulting in (often absurd) situations where the doctor has to choose between delivering good quality care for the individual patient and making the 4 hour taget

3: From the UK experience, if there is one solution to the crowding-problem, it is trying to fix the access block / exit block problem on all levels of care

https://emergencymedicinecases.com/ed-overcrowding-access-block-causes-solutions/

4: The COVID19 pandemic is unique in modern medicine and has caused problems into an already suffering healthcare system in Stockholm.

5: Emergency Medicine as a speciality is in [our hospital] undervalued / underappreciated, and our expertise is sadly utilized in a suboptimal way.

6: Daily education sessions for Emergency Phyisicans, indtroduction of new workers in the ED and making information for front-line workers (like guidelines that are easily searchable for management of “standard patients”) should be prioritized much more. If not the current status quo with difficulty with “handling undiminishable uncertainty” and as a result a “more is more” culture prevails, as it is always easier to “do more” when you are uncertain (with increased wait times and overdiagnosis as a result)

7: Due to the complex nature of healthcare and due to the fact that the 4 hour rule is the only thing being measured, the current tendency for longer waittimes may be outside of our control (i.e “input”-problems and “output”- problems from primary care and the rest of the system = Access block). Patients are unable to seek care according to the LEON-principle and we are unable to arrange followup for them (as accces block is the reason they are here with us right now). Resulting in a situation where the emergency department is utilized for something it was not designed for – taking care of sub-acute or chronic problems because of acccess block in the system and we are “the only ones who are open”

It is known in the emergency physician group, that the waittimes has gone up from 2018-2020. This coincides with the starting up of emergency medicine in [our hospital]. We would like to draw attention to the discussion of causality Vs correlation. Other events such as 1) The closing down of NKS, 2) the general problems in Stockholms healthcare system, 3) COVID19 and the complexity of this entire pandemic in healthcare.

8: Communcation, transparency and a “blame instead of learning”-culture: In order to fix challenges in a complex system like the healthcare system, clear communication with front-line workers needs to be a priority. Any vital decisions needs to be discussed with them. Critique should be met with open arms and not with condemnation.

For more on how to built a good “psychological safe” culture in our hospital, I’ve made several blogs about this. The main messages are

- Transparency and feedback (see my feedback blogs)

- Vulnerability loops (see “The Culture Code”, Daniel Coyle)

- Learn-not-blame culture (see Sidney Dekker and Martin Bromiley)

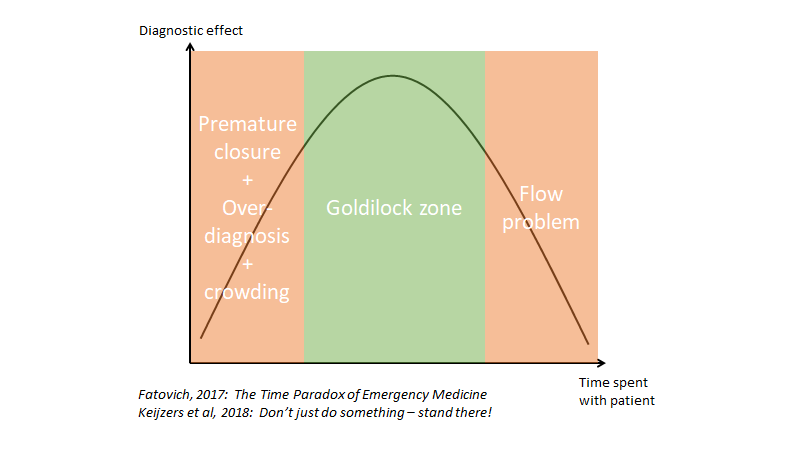

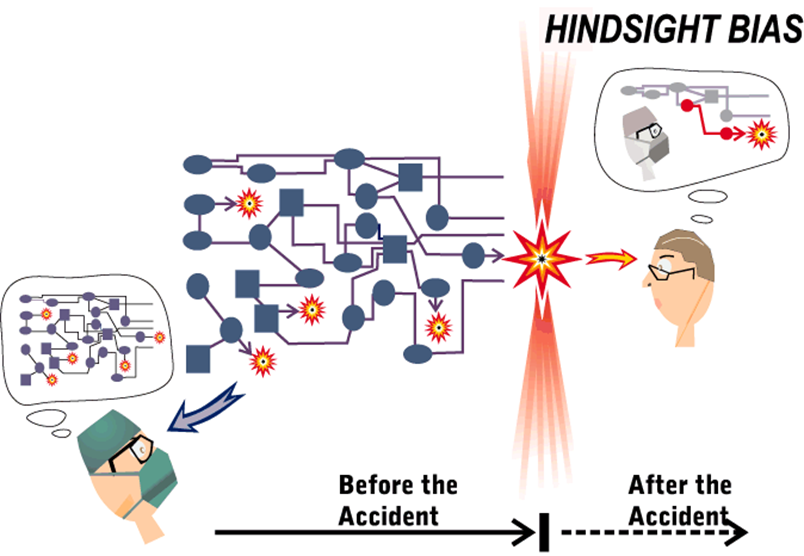

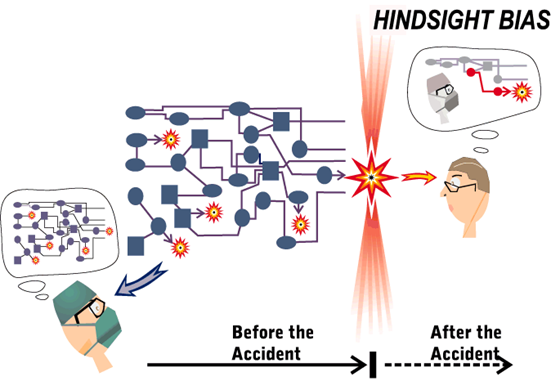

- Daily meetings where the above can be “grown”: for instance – case of the day, where someone brings a case (doesn’t have to be an amazing one), and it is especially good if a senior brings it an tells the team, that he / she made a mistake (first part of a vulnerability loop). At this point it is essential that you go through the case prospectively (not through the retrospectoscope – se figure underneath). Learn do dissect a case cognitively soundly and probabilistically (i.e with what croskerry calls “cognitive dissection” – see for instance Judith Bowens brilliant article, or Simon Carleys brilliant lecture, or SIDM (Society for improving diagnosis in medicine) videos. This does not have to take more than 5-10 minutes per case. When the case is done, something magical has happened: people have bonded, and you are a step closer to a more healthy culture (the last part of the vulnerability loop is closed when people understand / show through the case, that they also make mistakes).

- These additional meetings will also add to the cultural value amongst the group (belonging + creating a goal + feedback/psychological safe culture = all the goals in good and healthy cultures)

COVID19 specific problems:

Complexity and the C19 patients: During the C19 pandemic, it has been enforced that patients are not allowed to leave the emergency department without being put into either of the following categories: C19-positive or C19-negative. As per guidelines of [our hospital], this often requires consultation with an expert in infection medicine. Several time-delayes can be found

- If a patient comes through the “LVT” (luftvägstriage), and everything is done right away (usually takes 30-60 min for a USK or SSK to make the patient come to this point), then the C19 “snabbtest” takes >120 min (not uncommonly >180 min). No matter how much preperation the doctor has been doing for the moment the C19 test comes in, the result of it will determine the ease with which the patient can be placed. A C19 positive patient is easily placeable. A C19 negative (which has increasingly become the norm as C19 patients has dwindled) are harder to “rule out”, and often requires either consultation with experts or CT thorax. Either of which are bottle-neck situations, and it is impossible to reach the 4 h limit, when this decision has to be made at the 3:00-3:30 h point when the C19 test comes back. A C19 “indetermined” patient are the hardest to place – especially if they are critically ill (These are patients with C19 negative, but still a moderate post-test probability, and CT that is undertermined. They cannot be placed on IMA, too sick for any other placement, and IVA is then the only other spot for them – this always greate lengthy discussions even with the involvements of the experts at the “medicine desk”).

- Most of the patients we see right now are C19-negative, but has gone through the LVT and therefore depending on their presenting symptoms, it can often be hard to “rule out” these patients for C19 without advanced help (consultation, CT) – as per the arguments stated above, these decisions has to be made before the C19 test comes back in order to stay within the 4 h limit.

A few general problems with the 4 hour rule

- Is not a measure of quality for the individual patient (and creates opportunity cost-effect when we focus on it too much)

- Is non-sensical for the doctor and creates prioritiy issues that – if followed – can be ethically problematic: In the extreme case where the doctor choose to prioritize the 4 h rule only, there would be no reason to see the following patients (these are usually the patients that the emergency phyisician sees as they are not easily put into any box of “medicine”, “surgery” or “ortho”)

- Complex patients i.e frail elderly with little / no ressources or patients with a history of psychiatric illness or drug abuse; patients without a home and other social issues (takes too long, and requires to many ressources)

- Patients that “falls between” the different traditional speciality groups (i.e broken hip with infection and headbleed)

- Functional (FND) patients / pain patients and other patients that require no test, but communication and time and could not easily be turned around by the triage-doctor (for a reason usually)

- Patients who has waited for 2-3 h before seen. These patients are in high risk of breaking the 4 h barrier, and are therefore on paper illogical to care for

- Patients who requires an interpreter

- Does not take into account the “complexity” of the patient (complexity is the new acuity) – the NEWS-score, we guess, does not correlate very well with wait times. An obviously sick patient is easyer and faster to handle, than the multi-complex elderly, drug-abusing patient with a psych history and with multiple “specialities” involved (i.e broken hip = ortho + CRP 200 and fever = i.e medical + C19, and headinjury = surgery).

- Does not take into account other bottlenecks than doctors (i.e nursing staff)

- For the above stated reasons, taken to the extreme, the 4 hour target will create an “reverse robinhood” absurd situation, where the healthiest and sickest and non-complex patients in the ED are prioritized

General challenges in [our hospital] with keeping within the 4h rule timelimit

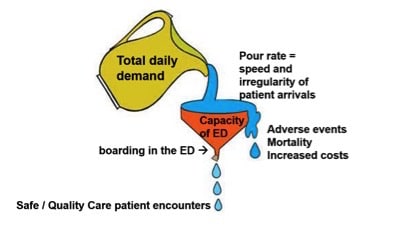

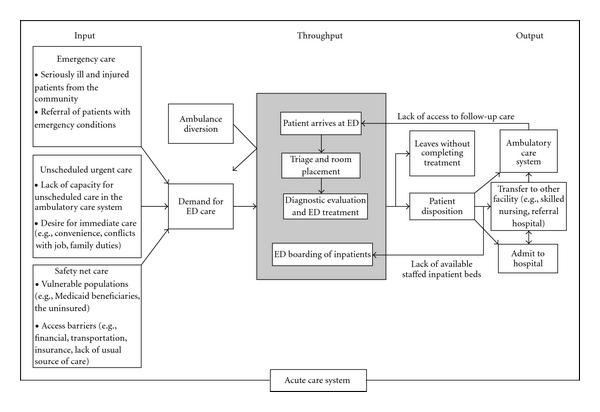

It is often easiest to view crowding problems in input-, throughput- and output problems (see figure 1, Asplin et al)

Input

- The problems of the Stockholm system, I have written about extensively in my danish emergency medicine blog (https://akutmedicineren.dk/erfaringer-fra-stockholm-del-1-det-frie-vaardval-og-lande-vi-sammenligner-os-med/ ), and as this is generally seen in [our hospital] as being “outside of our control” I will not comment further on this aspect

Throughput

- Introduction of new staff is sub-optimal. Most new staff has to be taught the basics of emergency medicine, has to be able to take “larm” no matter their level (with or without help), and be thoroughly informed on the most important guidelines, phone lists etc

- Doctor triage:

- The doctor triage is a concept not adapted in most hospitals: if the doctor in the triage position cannot do either of the follwing 1) Sent people home directly without any tests / minimal tests as a primary care physician, 2) Choose the right paraclinical exam measures outside of “standard blood samples” (i.e CT scan for thunderclap headache within 6 h, so that it doesn’t have to become a CT -> LP when the 6 h limit is passed), their utility probably of limited value in the current format. The doctor-triage does not ad any value to the care, and only is another step for the patient to go through (which is a nusiance to the patient). During the night time when there is no doctor triage, there are no bigger problems if the nurses are triaging

- Amount of doctors in the triage: Triage doctors are often abundant compared to the amount of VL. It seems that ressources could be utilized more effectively

- Expertise of triage doctors: Emergency Medicine triage is a dinsticntly emergency-medicine expertise, and as any other expertise-area (like radiology or open surgery), it cannot be expected to be done by any kind of doctor. Despite this, all traits of internal medicine are used as experts in the triage. Optimally the expertise required would be that of either primary care physicians or emergency physicians.

- Handoff-situations:

- Optimally in a system there is a “pull”-effect when handing off patients. The doctor coming in, will go to the VL and take over the patient from the VL, that cannot be finished within the timeframe of the work-hour for the doctor signing off. This does not happen in [our hospital], and as a result, it is unwise for someone wanting to go home in time, to take on complex patients in the latter of their shift.

- The above statements is especially true for emergency physicians – as no emergency physician with emergency physician competences is taking over, many patients that are “in between the specialities” are impossible (or at least very hard) to give to any medical, surgical or orthopedic VL.

- The above results in “complex patients” having longer wait times especially around sign-off time.

- More is more culture:

- It is emergency medicine expertise to order the right amount of tests in the ED-population. As it is not Emergency physicians choosing the tests, but merely following up on them, the more is more culture cannot always be effectively mitigated by the expertise of emergency physicians. This often is one of the main throughput drivers of long wait-times.

- Emergency physician on the spot

- Complex patients with multiple problems usually require consultaiton with multiple specialities. If a senior ED physician was present at all times, it would probably be possible to reduce the amount of interactions with consults

- The expertise of a senior emergency physician cannot be effetively replaced by other specialities – especially when patients do not fit the “traditional boxes” of the specialities

- “vårdlag” and wait times

- The placement of patients on VL cannot be random: The capacity of the VL has to be taken into consideration when placing a patient there. If for instance a VL has two patients, and the triage wants a patient who has waited for a long time, to go into the same VL, then that exact patient may end up waiting a longer time, than if the triage had waited for a VL who could see the patient at once

Output

- Responsibility of the department:

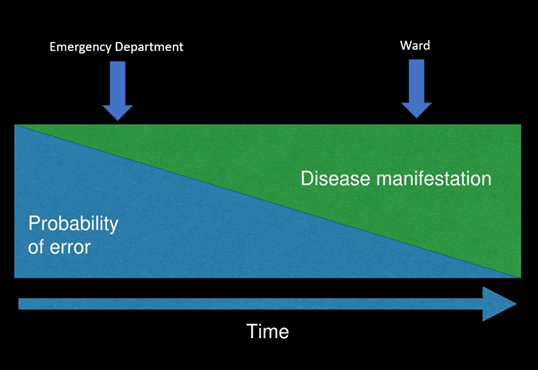

- The wait time in the ED are closely related to whehter there is someone taking care of the patient in the department where you are admitting. The more secure the emergency physician can feel with sending up a patient “before knowing the final treatment”, the sooner the patient can be sent up. Unfortuneatly perfection is often expected from the emergency physicians, and a culture of looking at cases through a retro-spective view (“why did they do this!?”), instead of a prospective (“I wonder why a skilled collegue has made this decision with this patient?) (see figure 2+3)

- The discussion above makes it hard to know from the ED whether the patient is supposed to have a “final” treatment plan in place before being moved up to the department, or if “pieces of the puzzle” can be missing and a doctor in the department can follow up. Without a clear way to work this problem, we are in the ED prone to do more, as we are uncertain if the patient will be followed up in the department before tomorrow.

- Hard to find a department for the patient:

- It is no secret that “VPÖ” rarely works as it should and rarely is updated. During COVID19 when a coordinating doctor was in place, who called the departments in the morning to get an real-time overview, and shared that information with the ED, and took responsibility for the job of getting the patient admitted, was a huge help .

- VPÖ [the overview of beds in the hospital] often creates an illusion of there being lots of space for patients, when in fact a lot of the space is promissed to patients from other hospitals, other departments or simply has not been updated. This creates a in-efficient and time-consuming task for each doctor wanting to admit a patient, having to call around to several departments (often more than once) in order to find a spot for the patient

- Follow up

- Many of the patients in an emergency department are there because of failure of the primary-health care provider (i.e. access block, og lack of trust). In a system where the primary provider can follow up on the patient seen in the ED, faster, you do not have to do as much work on the individual patient in the ED. In the UK this problem has been adressed with sub-acute outpatient clinics (https://www.rcem.ac.uk/RCEM/Quality-Policy/Clinical_Standards_Guidance/RCEM_Guidance.aspx?WebsiteKey=b3d6bb2a-abba-44ed-b758-467776a958cd&hkey=862bd964-0363-4f7f-bdab-89e4a68c9de4&RCEM_Guidance=3 ) , that could be led by emergency physicians

- Many follow-up pathways for standard patients are hard to find in [our hospital] (i.e where do vertigo patients go for follow up? Low risk chest pain patients? Etc). These pathways could be made more clear and standardized for certain groups of patients.

- Geriatrics from the ED

- It takes a lot of time to sent a patient to a geriatric department from the ED and often it’s not worth investing the time, if we are to keep the patient within the 4 h limit. Several reasons for this

- Geriatric clinics only accept a very select group of patients (i.e has to be diagnosed or close to diagnosis)

- The transport often takes a long time getting to the patient, in which time the patient often breaks the time-barrier

- There is no clear consensus on which geriatric hospital takes which patient – often an ED doctor is sent into a spiral of calling different hospitals, explaining the SBAR / patient story to a geriatrician, just for them to say no.

- All geriatric departments demands a written “remiss” – this takes more time than admissions to [our hospital]

- It takes a lot of time to sent a patient to a geriatric department from the ED and often it’s not worth investing the time, if we are to keep the patient within the 4 h limit. Several reasons for this

Figure 2. Simon carley – Making good Decisions in the ED

Figure 3, Richard Cook and Sidney Dekker – hindsight bias

Referenes

- ED Crowding, RCEM homepage: https://www.rcem.ac.uk/RCEM/Quality_Policy/Professional_Affairs/Service_Design_Delivery/ED_Crowding/RCEM/Quality-Policy/Professional_Affairs/Service_Design_Delivery/ED_Crowding.aspx?hkey=cf5c370e-f312-465a-8770-c67588b7dd35

- https://www.stemlynsblog.org/making-good-decisions-in-the-ed-rcem15/

- Braithwaite, 2018: Changing how we think about healthcare improvements

- Sidney Dekker: Understanding human error, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crENdW2cGeU

- https://emergencymedicinecases.com/ed-overcrowding-access-block-causes-solutions/

- https://acem.org.au/getmedia/dd609f9a-9ead-473d-9786-d5518cc58298/S57-Statement-on-ED-Overcrowding-Jul-11-v02.aspx